Trip Report: Eastern Europe 2023-Nov

I spent 52 days overseas from November 2023 to January 2024. This is the train travel through Eastern Europe part of that trip.

Recently, a dear friend asked if I wanted to join them for a holiday in the Rhineland over Christmas, and I could hardly say No. The catch is that flights from Singapore to London in December are prohibitively expensive. However, December's older brother November offers many Scoot flights to Athens for only $320 SGD. It's then a brief, low-cost European flight onto London, or, in my case, an ornate series of connecting trips through Eastern Europe and then onto London. Let me tell you all about it.

Singapore (14 November)

The catch with a low-cost Scoot flight is that it leaves at one in the morning. But, flights at that time, I can report, are an ample opportunity to do your pre-flight preparation, such as packing, washing laundry and making the bed. In fact, as I draft this message from a student café in Transylvania (spoilers, this story is going to go to Transylvania) I am looking forward with barely concealed delight at returning home to Singapore and sleeping in a freshly made bed – its bountiful linen has been pressed and waiting for over six weeks.

In theory, flying late means that the airport will be quiet and you can sail through to your gate. Changi on the night of Tuesday Nov 14 was surprisingly busy. However, Changi at it’s busiest is still only 30-45 minutes from check-in to gate. Enough time to buy a snack, because this flight does not include meals.

Time to scoot!

Athens, Greece (15 November)

The last time I was in Athens it was a dreary May Day. I practically cried out "M'aidez! Help me, it's dreary!" This time, though, Athens came out to shine. Streets were thrumming, cafes were bustling, but enough travel writing pablum - Athens was great!

I stopped by the National Historical Museum where the emphasis is very much on the National. Ancient Greece had a lot of charming inventions, but nationalism wasn't one of them - guess you didn't think of that one, Pythagoras! This is why the National Historical Museum has absolutely no ancient history, togas or tyrants.

Anyway, the National Historical Museum starts with the fall of Byzantium, when Greco-Roman history ended and Greek national history began. The Greek community then lived entirely under the Ottoman empire. The Ottomans also didn't invent nationalism, so the diverse cultural communities of the empire were granted limited internal self-government on the basis of religious rather than national identities. Yet the church was the only institution that encompassed and governed Greeks as Greeks. So Greek nationalism began in the embryonic form of the Greek Orthodox religious community under the Ottomans. Or so my reading of museum placards would imply.

The National Historical Museum from the outside-in and the inside-out.

The Museum goes through the various stages of the Greek national consciousness: Ottoman rule, the Greek War of Independence in the 1820s, its consolidation, growth and expansion across the 19th century, the Great War, brief accomplishment of the Megali Idea and its sudden collapse in the Anatolian Catastrophe, when Turkey drove Greece out of Asia Minor following World War I. The first major wave of Greek migration to Australia is said to have been driven by refugees fleeing that catastrophe, though I can't corroborate this. The Museum itself was the Old Hellenic Parliament from 1875 to 1932. The parliamentary chamber was where the Government conducted the Trial of the Six in 1922. 'The Six' were officials held responsible for the Anatolian Catastrophe.

A few blocks from the National Historical Museum is the Cathedral Basilica of St. Dionysius the Areopagite. It's a rare Catholic institution in an Orthodox city. The titular Catholic Church in Athens was founded circa 800 AD, with a few dis-establishments and re-establishments over the centuries as Crusaders came and went. The neo-Renaisance building was designed pro-bono by Lysandros Kaftanzoglou and completed in 1865. Its interior was unsurprisingly stunning and well worth a stop.

Amalia of Oldenburg was indeed Queen of Greece at the time, but I've found no record that the church was built for her, let along by her.

This church loves cats, it's a cat-aholic!

For those wondering what’s this Areopagite in the Cathedral Basilica of St. Dionysius the Areopagite, it’s one of the rocky outcrops in Athens. The Acropolis is another such outcrop and the highest in Athens (it’s in the name. Akron means highest point, and polis means city). The Areopagus translates as ‘Hill of Ares’ because it's said that the Gods charged Ares for murder upon that hill northeast of the Acropolis. If you visit the Acropolis you can stop at Areopagus on the walk down. At the risk of alienating my polytheist readers, Ares was probably never tried upon the hill, the myth was invented to lend gravitas to the legal proceedings that did take place there – usually homicide, wounding and burning olive trees.

Down from the Catholic Church is the (modern) Academy of Athens. It's so modern it was built in 1926, roughly 2,313 years after Plato founded the original academy. Just down from that is the Vallianeio Megaron (National Library, pictured).

After that, my interest in sight-seeing was history, so I wandered down a number of charming lane-ways. Athens has fantastic lane-ways. If you have a fair weather day to unwind, you can't do better than putting on some comfortable shoes and going for a stroll. I stopped by Atlantikos for a lentil and anchovy salad with a glass of Mythos. It was perfect after a long flight.

OK, ChatGPT, you got the bit about Athens right.

Bucharest, Romania (16 November)

I caught a late flight from Athens to Bucharest, Romania. The signs in Romania felt eerily familiar because Romanian is a romance language like French and Italian. For example, station is gara in Romanian but gare in French (and gar in Turkish, which isn't a romance language, but they did borrow the word from romance languages). Despite Romania's history in the Warsaw Pact, its literary tradition is romantic, not Russian, so you won't find any babushka clutching a worn copy of Dostoevsky here.

Despite this linguistic head-start, I was totally lost in the language but managed to find the right bus thanks to some helpful convenience store clerks. You don’t even need a bus card you can just tap on with a bank card (I used my Wise).

In the morning I went to the Romanian National Military History Museum. That place really emphasised the history. The first exhibit started with cases upon cases of palaeolithic flint arrowheads found in Romania and goes from there.

Following the palaeolithic section comes the Romans, who play a large part in the history of Romania. Emperor Trajan conquered what was then called Dacia in 102 BCE. This made up the bottom half of modern Romania. Despite the fall of the Roman empire, Romanians preserved their Latin based language amid waves of migration. Romania as such united in 1859 as the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. However, in 1862 they rebranded as the Romanian United Principalities because these polities shared common descent from the Romans – hence Romania.

Minor sidebar but the maps in the Romanian National Military History Museum were tactfully ambiguous about Moldovan independence. Whenever a map drew political boundaries of current day Romania, it used the political boundaries of current day Romania. However, when the map simply drew the geographic area of Romania, no political borders, it would often extend up to and including Moldova and Bucovina.

I found the WWII section most interesting because during WWII Romania fought on both sides. In 1940 they joined the Axis and sent troops to the invasion of the USSR. When the war went badly, they switched to fight for the Soviets and the same army that invaded Russia fought alongside Russians to invade Hungary and Czechoslovakia. I only learnt this indirectly at the Museum. There’s no explanatory text for any of the displays. You simply walk out of one room with photos of Romanians posing with German soldiers then enter the next room with photos of Romanians posing with Russians. I had to figure all this out on Wikipedia.

The best part of the museum is that out the back they have old Romanian and Russian army vehicles lying around. They’ve got a railway gun, helicopters, missiles, and tanks. The T-34 with the front cut away was interesting. Sadly there was no cafe, but the fascination with military hardware more than fueled my exploration.

I like big guns and I cannot lie. You think the black and white photo was during WWII? Nope, it was 2001.

I didn't have long in Bucharest so I headed to Gara București Nord (told you it's a romance language) and caught the train through the Carpathians to Brasov.

Brasov, Romania

In late 2023, a railway lobby group released a map of sleeper trains across Europe. I think sleeper trains are great fun, but the trick is to book one that covers enough distance that you don’t have to wake up at 4am because the conductor tells you ‘we’re here, get off the train’. For this particular trip, at this time of year, in these countries, the only sensible night train was from Brasov to Budapest in Hungary. I caught a domestic train from Bucharest to Brasov in Transylvania to link up with the night train.

The local train snaked through the mountains. It was clear but cool in Bucharest, but when we passed the mountains into Brasov the weather turned grey and chilly. I found a student café at Brasov technical university to write this draft, then boarded the train to Budapest.

Fields outside Bucharest (left). Town in the Carpathians (right). Welcome to Pennsylvania Transylvania.

Budapest, Hungary (17 November)

The night train to Hungary was taxing, but did not detract from the delight of reaching Budapest (or, budɒpɛʃt if you prefer to be precise and understand IPA). The city used to be three towns: Buda, Óbuda (Old Buda, to the north), and Pest, before they were merged in 1873.

Two cities, both alike in dignity (Map)

I stayed in the Pest side of Budapest. Pest follows a grid layout where streets run north-west to south-east. My hotel was near Oktogon, the intersection of the Grand Boulevard and Andrássy Avenue, which is in the unsurprising shape of an octagon. The intersection bore the unfortunate name of Mussolini Square from 1936 to 1945, when Hungary was ruled by a fascist admiral (despite being landlocked!). From 1945 to 1990, the intersection was named the November 7 Square in honour of the October Revolution (if that's confusing, blame the Julian calendar). After the fall of the Berlin Wall it was renamed to the accurate-albeit-anodyne Oktogon.

The Oktogon and its surrounding environs

Coming off of Oktogon is Andrássy Avenue (Andrássy út for the Hungarians), a World Heritage Listed boulevard of neo-Renaissance buildings. The street is named for Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy who was a big supporter of its construction in the 1870-80s. After the Hungarian Uprising post-WWII, it was re-named Stalin Avenue (Sztálin út), then the Avenue of Hungarian Youth in 1956, and People's Republic Street the year after that. Once the Berlin Wall fell, it was restored to Andrássy Avenue. Despite its communist history, the avenue is one of the most expensive streets in the world in terms of property values.

The Hungarian State Opera (left) and Drechsler Palace (right) face each other across Andrássy Avenue.

West along the avenue is St. Stephen's Basilica is a very ornate, very Catholic church. It's named for St. Stephen, the first King of Hungary and who was crowned on Christmas Day in the nice round year of 1000 AD. King St. Stephen is (mostly) buried elsewhere, but the Basilica does house his right hand, his most kingly of hands.

The place was thronging with tourists when I went (and not just for the right hand) but very much worth going despite the crowds. It's a gorgeous neo-classical building with an arresting ceiling. Although the church is Catholic, the floor plan follows a Greek Cross layout, rather than a Latin Cross layout like St Paul's. There is the option to go up top and enjoy the panorama of Budapest, which I highly recommend.

It's a great church, you've gotta hand it to 'em.

Further west, past the Church and Széchenyi Square is the Széchenyi Bridge. Built by William and Adam Clark (no relation), who based it on the design of the smaller Marlow Bridge in Buckingham. It was the first permanent Danube crossing in Budapest when it opened in 1849.

The bridge is pointedly not named Clark Bridge though, because it's named for its patron, István Széchenyi, a well known figure to listeners of the Revolutions Podcast's series on 1848. During the Revolution, the Hungarian parliament instituted democratic elections, which the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph (of WWI fame) revoked, prompting the Hungarian Parliament to declare independence. The whole independence thing didn't last long and soon Hungary was back within the fold of the Austrian Empire. Once all that had settled down, the bridge was officially opened.

Walking along the Buda-side of the Danube affords a wonderful view of the Hungarian Parliament Building. After the defeat of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, Hungary was ruled by a military dictatorship from Vienna. However, in 1866 the Prussians beat the Austrians in the Brothers War, costing Austria its lands in Venetia and a lot of money. The Hungarians used this as leverage to negotiate the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, which restored the liberal democratic reforms of 1848. Emperor Franz Josef later remarked that "There were three of us who made the agreement: Deák, Andrássy and myself" - the same Andrássy of Andrássy Avenue.

Under the compromise, the Austrian Empire would become the Austro-Hungarian Empire, ruling Hungary merely in personal union with Austria and affording Hungary its own liberal democratic constitution. The compromise was, however, deeply unpopular among Hungarians who saw it as a betrayal of Hungarian independence. The ruling Liberal Party, who negotiated the compromise, was so unpopular among Hungarian voters that they could only retain power through the electoral support of Hungary's sizeable ethnic minorities.

Still, Hungary was a democracy again. When the towns of Buda, Obuda and Pest united in 1873, the parliament took this as an occasion to commission a new parliamentary building that reflected Hungary's sovereignty and prestige. They ran an international design competition which the Hungarian architect, Imre Steindl, won handily (the runners up got to design the Ethnographic Museum and Ministry of Agriculture, which face the Parliament). Steindl's neo-Gothic design of the Parliament was inspired by the Palace of Westminster, which the Hungarian parliament was keen to emulate, communicating their commitment to Western Europe and liberal democracy. However, construction was a bit of a nightmare, running from 1885 to 1904, by which time had Steindl had already gone blind and, later, died.

Hungarian Parliament, I like your angle!

Walking opposite the Parliament and around its grounds underscores how stunning the design is.

Bratislava, Slovakia (18 November)

The next morning was crisp and clear, allowing the sun to stream down the Budapest boulevards. I could not stay, however, as I had a train to Slovakia and then the Czech Republic.

Budapest in morning

Bratislava, formerly 'Pressberg' under the Austrians, is the capital of Slovakia. The city is very close to Vienna, only 54 kilometres apart, which is the third closest pair of capitals in the world, after Rome / Vatican and Kinshasa / Brazzaville. Bratislava is also close to Budapest, which I suspect explains why so much Hungarian politics happened in Bratislava. Here, St Martin's Cathedral was the coronation church of Hungarian monarchs from 1563 to 1830. The Hungarian Parliament also almost always convened in Bratislava / Pressberg over the same period.

In all my wanderings in Bratislava, I never once saw a street performer.

Bratislava was a joy to walk around. Like much of Europe, the old town streets are completely pedestrianised, although this one was filled with a strangely familiar cafe slogan...

This one jumped out at me:

We love to make coffee for the city that loves to drink it

I first heard this slogan at Market Lane Coffee in Melbourne but here in Bratislava it appeared at Five Points (which was great, by the way, the coffee was just lovely). This led me down a Google-hole where, apparently, the slogan is also in Downtown Boston and in Warrenville, South Carolina. From this we can only conclude that there are many cities who love to drink coffee, and no shortage of cafes that rejoice in enabling that behaviour.

I was only in Bratislava for lunch and then it was back on the train to Prague.

Prague, Czech Republic (18 November)

I arrived quite late in the Czech Republic. Or should that be Czechia? The roll-out of this new nomenclature has caused a lot of confusion. Word has it that not everyone knew that this was a thing. As reported in the media at the time:

"It’s a little confusing. Nobody calls it Czechia, I don’t know why,” said Lukas Hasik, 40, a software engineer" - Guardian

"The prime minister of the Czech Republic was halfway through an interview in March when he was told somebody had officially changed the name of his country to Czechia" - WSJ

Either-way, I reached a capital city in lands once called Bohemia. There was just enough time to leave my bags at the hotel and go for a stroll through the city centre. As much as I remarked that St Stephen's in Budapest was touristy, Wenceslas Square was overflowing with British bucks nights. Zero stars, would not be surrounded by obnoxious British bucks nights again. I got a late dinner and then hit the hay.

19 November

Come dawn, the clouds had rolled over Prague and the Brits had drained out. The streets were much more pleasant to walk alone in the misty rain. By the way, did you know that there have been not just one, but two defenestrations of Prague? The first was a tragedy, but the second seems like carelessness.

I cut through the Old Town Square to the Manes Bridge and crossed over to the right bank.

On the right bank is the Lesser Quarter (Malá Strana), home to Prague Castle, a set of Pissing Statues (their words), and Prague's narrowest street. Just south of Manes Bridge is Kampa (Campus), an island in the Vltava river separated from the mainland by the Čertovka (Devil's Canal). The island was only named Kampa in the 17th century in reference to the Spanish soldiers stationed there. The origins of the canal and the island are a mystery, but it is said that they were built by the Knights of Malta in the 12th century.

The Knights of Malta are an interesting bunch. They were founded in the State of Jerusalem during the Crusades. Their mission was to militarily defend pilgrims in the Holy Land, administer captured territory and to run a hospital. After the Fall of Acre in 1291, ending the last crusader state in the Levant, the Knights moved to Cyprus and then to Rhodes where they formed a multicultural military order dedicated to taking the crusades to the waves. There the Knights enthusiastically plundered Muslim shipping until 1523 when Suleiman the Magnificent did a magnificent job capturing Rhodes after a six month siege. Things looked bleak for the Knights until Emperor Charles V benevolently granted them the island of Malta as a base to continue their seafaring ways. From 1651 to 1665 the Knights went through an 'American phase' when they purchased four Caribbean islands from the French and then sold them back. In 1798 the Knights lost Malta (possibly behind the couch) when Napoleon invaded on his way to Egypt. The Swedish Government offered them Gotland in the Baltic (yet another island) as consolation, but the Knights declined because it would have meant renouncing their claim to Malta. You'd think that would be the end, but the Knights limped on as a military order in exile. They were still around by the end of WWII when Italy, forbidden to maintain an air-force under its terms of surrender, transferred its aircraft to the Knights, making them briefly one of the largest military air-forces in the world (Italy got its planes back in the 1950s). Nowadays, the Knights are still, technically, a sovereign state who's affiliates operate many charitable services we know and love, including St John Ambulance. But I digress, I think we were talking about Prague?

There's a little Venice inside us all.

Within the Lesser Quarter is the western end of the Charles Bridge, one of the oldest and largest medieval bridges still standing. Until 1841 it was the only way to cross the Vtlava. The Charles Bridge is one of the real big hitters of Prague sight-seeing. You may not know the bridge, but you very likely know the stations along the bridge depicting saints, rulers and good doggos who deserve a pat.

Here we see in close-up the brass-work at the base of certain stations. Over the years, travellers across the bridge have paused at the reliefs at the base of the statue of St. John of Nepomuk to contemplate their meaning, reflect on their lives, and to give a good boy a rub behind the ears, which you may have seen online.

Obviously the dog is a good boy who deserves a pat, but is that really the case for all the other reliefs?

Just over the Charles Bridge, through the Old Town Bridge Tower, onto the left-bank in the Old Town, lies the St. Francis Of Assisi Church, named for the same Saint as Pope Francis. The church is the headquarters of the Knights of the Cross with the Red Star, who from the 1250s operated a local hospital and were the bridge keepers of the Charles Bridge.

East of the Church is the Karlova (Charles Street) a charming thoroughfare through the equally charming alleys of Prague's Old Town. Head down there then hang a left through the Klementinum and you'll find the much photographed Girl with Paper Swallow on the wall. The statue was installed in 2005 by the Polish sculptor Magdalena Poplawska, who studied in Prague. I legit cannot find any interesting trivia about this one. People just seem to think it's neat :shrugs:

I backtracked from the Girl with Paper Swallow and passed the New City Hall, proudly flying Czech, European and Ukrainian flags (though the wind was down that morning). I then went north to the old Prague Jewish Quarter. There's a self-directed audio tour of the synagogues and museums there that I highly, highly recommend.

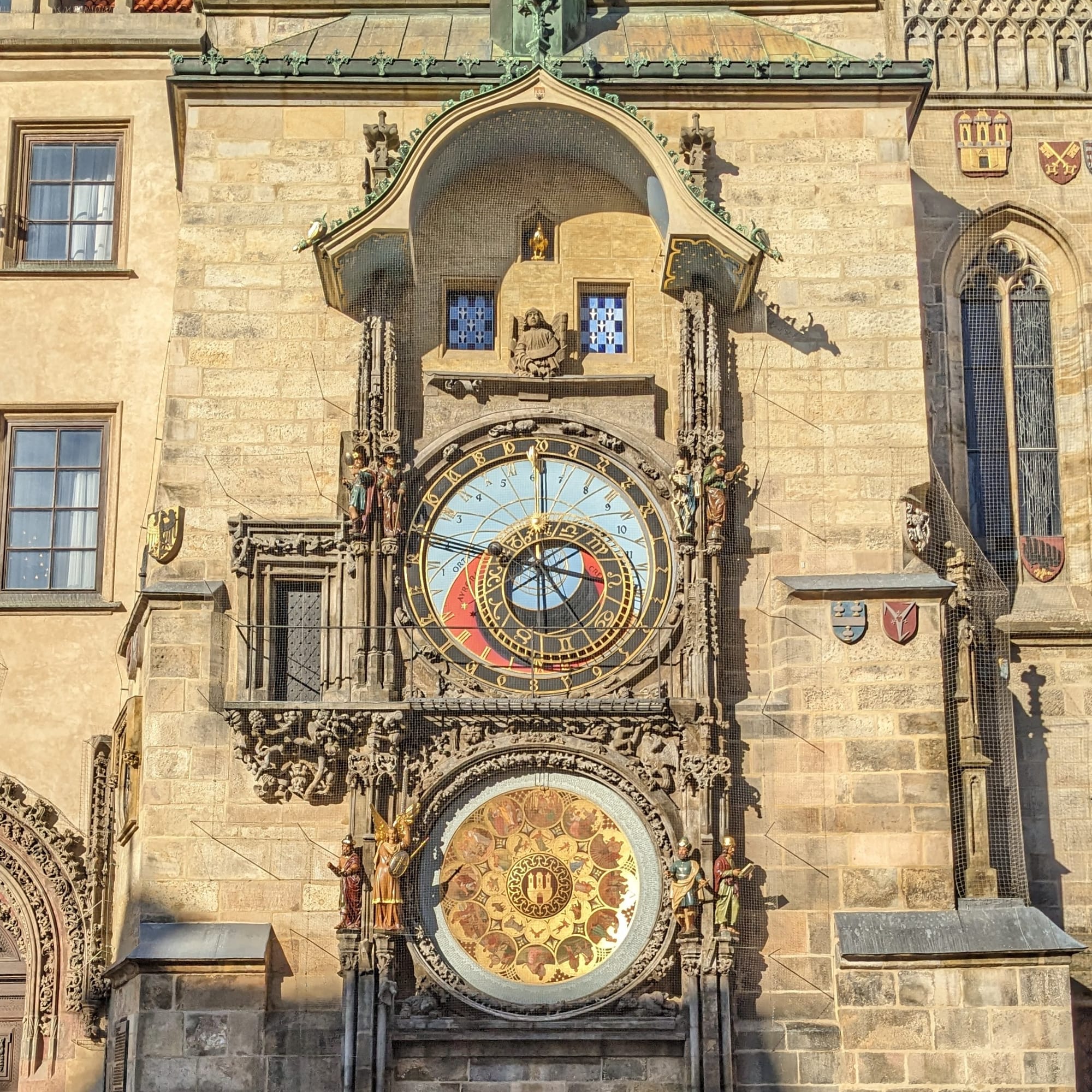

After the tour, I returned to the Old Town Square. With the sun out and puddles beginning to clear, tourists had returned to the Astronomical Clock. The clock is a tourist magnet because it's the oldest clock in the world still working, and the third-oldest still existing, dating from 1410.

The clock itself is laden with symbolism. The astronomical dial - the upper circle - indicates the location of the sun and moon, as well as the zodiac, daytime, nighttime, the equator and the tropics. The clock is flanked by Catholic saints and every hour figures representing the Apostles come out and move. A figure representing Death strikes time when they do. The lower circle is a calendar representing the months. Overall it's a beauty of a clock.

I packed my bags and returned to Prague station for my train to Krakow.

Kraków, Poland (20 November)

Poland was the only country whose weather truly failed me on this journey. The rain fell in droves, it descended in a fine mist, and sometimes it did both, but the day was never without rain. Please forgive me, therefore, if I draw upon the internet for photos that do justice to Kraków's beauty.

The Stare Miasto (Old Town) is a real pleasure, well worth fetching an espresso, camping beneath the statue of Adam Mickiewicz and engage in people watching. Adam Mickiewicz is an interesting figure, said by some to be Poland's greatest poet. He was one of the "Three Bards" who gave voice to Polish nationalism from 1798 to 1859. All three lived in exile (like another famed Polish writer, Joseph Conrad), composing tragic plays and poetry that reflected Poland's partition between Russia, Prussia and Austria (more on that below).

In the Old Town's Market Square is St Mary's Basilica, a Catholic church built in the 14th century. The church is brick, and one of the best examples of Polish Gothic architecture, so much so that the Basilica is a model for churches built by the Polish diaspora around the world, particularly in North America. The Basilica, and Kraków Old Town writ-large, are UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Every day, on the hour, every hour, the Church plays the Hejnał mariacki (St. Mary's Trumpet Call) a five-note bugle call. The Hejnał is a well-known national symbol in Poland. It was played, for example, during WWII after the 2nd Polish Corps' victory at Monte Cassino. The playing of the Hejnał in Kraków, however, is always cut short. There the call is said to commemorate a bugler who, in 1291 (or thereabouts), sounded the alarm of a Mongol invasion approaching Kraków. The Polish bugler alerted the defenders to close the gates; however, the bugler was shot dead by an arrow, cutting the call short. The hourly Hejnał from St Mary's is itself cut short to honour that mythical bugler.

St Mary's Basilica was also, like many locations in Kraków, a setting in Schindler's List. In the film, Oscar Schindler approaches Leopold Pfefferberg in the Basilica to purchase black market goods.

St Mary's Basilica as filmed in Schindler's List (left, centre) and photographed during WWII (right) (link).

Opposite St Mary's Basilica is the Cloth Hall, a Rennaissance building that was once a hub of international trade. Foreign merchants imported spices, silk and wax from the East while Polish traders exported lead and salt from the Krakow salt mines. It's primary export though was textiles, hence the name. This was the period of Kraków's golden age beginning in the 1400s and ending around 1596 when the Polish king moved the capital from Kraków to Warsaw.

After its golden age, Kraków remained a cultural hub but declined in economic and political importance. During the successive partitions of Poland from 1772 to 1792, Kraków was assigned to Austria, while other sections went to Prussia and Russia. Poland was briefly, partially independent during the Napoleonic Wars. After 1815 it was re-assigned piecemeal back to Prussia, Russia and Austria in what is sometimes called the Fourth Partition of Poland. But not Kraków. In 1815, Krakow was made a strangely independent city-state, becoming a regional economic hub with a large and growing population, especially among its Jewish community, who rose to become thirty percent of the city's residents. However, an uprising in 1846 led Austria to invade and annex the city.

The differential effects of the Polish partition are still seen to this day, even in Kraków. The Prussian part underwent more extensive economic development and industrialisation, alongside colonisation by German settlers in western Poland, and a clamp down on political autonomy. The Russian part, called Congress Poland, experienced similar political repression, but no where near as much economic development. The Austrian part, which came to include Kraków, was not called anything, and was initially economically under developed and politically repressed. However, after Austria's defeat in the Brother's War, it granted its Polish territories greater political and economic self-governance (similar to Hungary, as we saw above), leading to limited economic growth and greater cultural influence among the Polish diaspora. This led Kraków to became known as the "Polish Athens", home to many Polish intellectuals until WWI and the restoration of an independent Polish state.

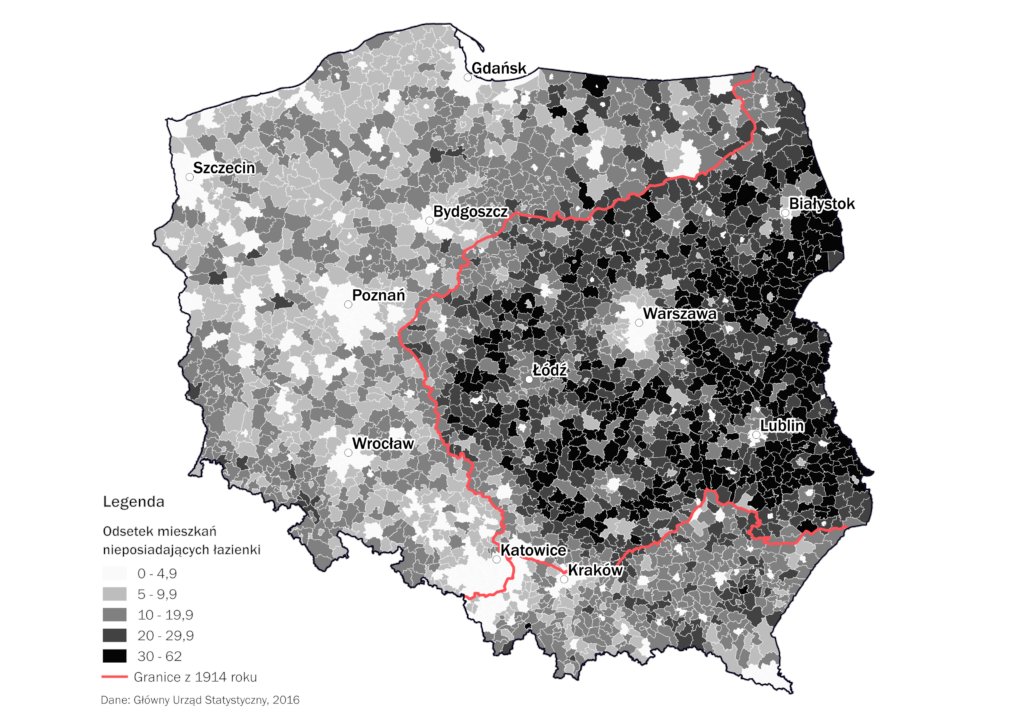

While the partition of Poland occurred over two centuries ago, the distinction between the partitioned sections continues to this day. The distinction is sometimes described as Poland A, the western, formerly-Prussian, economically developed parts, as compared to Poland B, the eastern, formerly Russian and under developed parts. For example, the proportion of buildings over 100 years old closely follows the 1914 borders that divided Poland between Germany (formerly Prussia), Russia and Austria. Kraków sits between the two, in some ways A and in others B.

Airport (21 November)

The next morning I caught my first ever RyanAir flight, this one from Kraków to Charles-roi, Belgium. Having done so, I now appreciate how low-cost this low-cost carrier can be. I forked out extra for my two carry-on bags, but a few over-optimistic souls were stopped at the check-in for having too much baggage. I was bound for a mid-level Belgian airport!