In 2013, I was having a hard time of it.

I graduated university in 2012. I completed an internship at a policy think tank. I then got a job in a big four consultancy, moved to Melbourne, met lots of people and put down roots.

But soon I felt completely underwater. I was unhappy that my work didn't use my data skills, and my managers were unhappy with what work I was doing. In tandem I struggled to turn my Melbourne acquaintances into Melbourne best friends. Soon I was pretty deep in depression and anxiety.

Over the course of 2014 I managed to turn my mental health around. I spoke to a psychologist. I took up physical exercise. My GP monitored my progress to ensure I did nothing drastic like quit my job or take up break dancing. And every night I wrote in my journal.

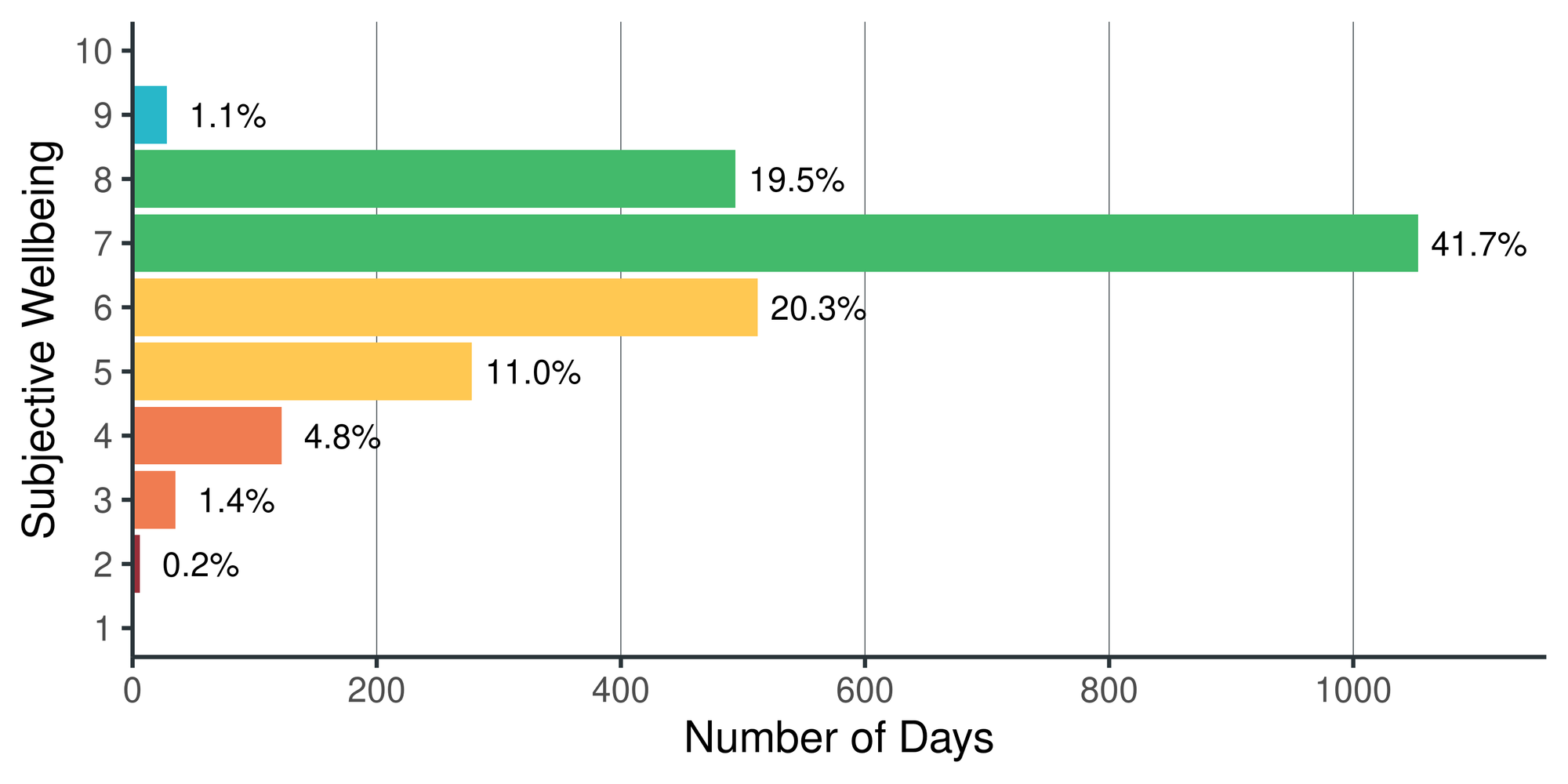

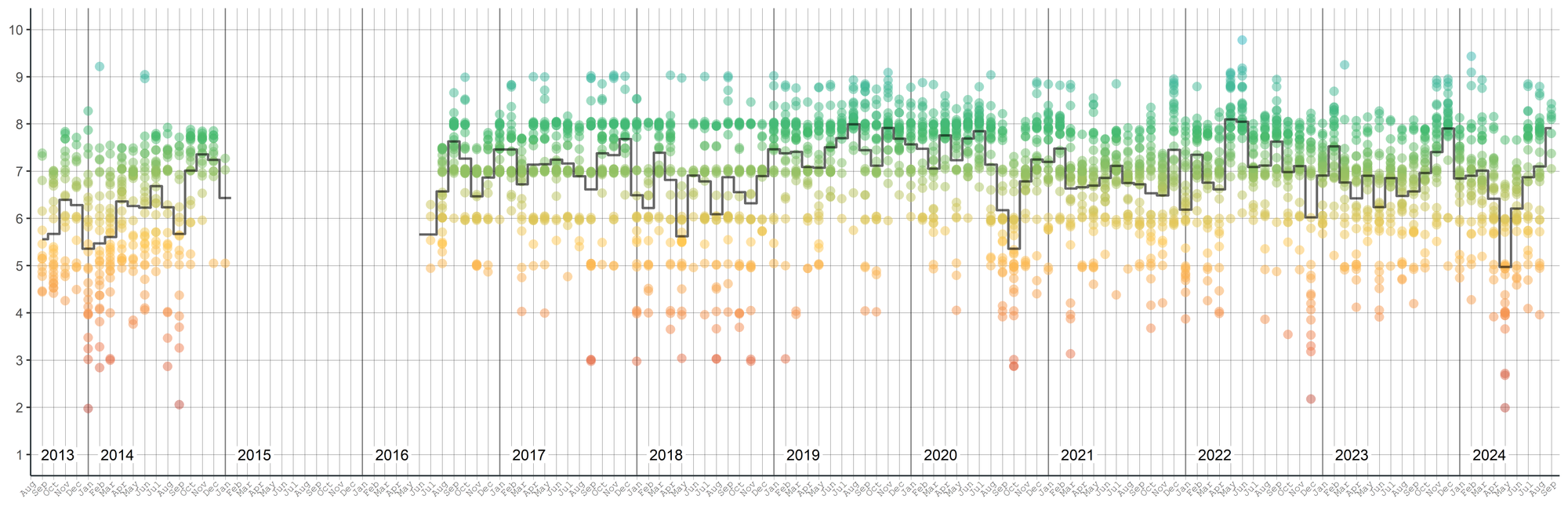

I wrote in my journal a score for how I felt that day. I crafted a scale from one to ten, where one was pure suffering, ten was absolute bliss and five was a balance of pleasure and pain. I counted my scores to know if things were getting better or worse. For seven months it got no better. Then things picked up.

Although I've put my mental illness largely behind me, I still keep my journal every night. As of late 2022 I've made 2,677 journal entries. Nearly four in every ten days were between a 7.0 and 7.9 (41.7%), nearly two-thirds (62.3%) were between 7.0 and the maximum of 10.0

This data has given me almost a decade's worth of insight into what has made my happier.

What led to happiness?

- Taking care of my mental health. If you are experiencing mental illness, the most important thing you can do is engage with professional care and keep at it. Most other things are of secondary importance.

- Making many good friends and spending time with them. Seeing my friends in person made a huge difference to my wellbeing. A huge difference. Living far from friends has been a lonely way to pass a few years. It's worth making real sacrifices to see your friends and make them a part of of your life, your effort will be well spent.

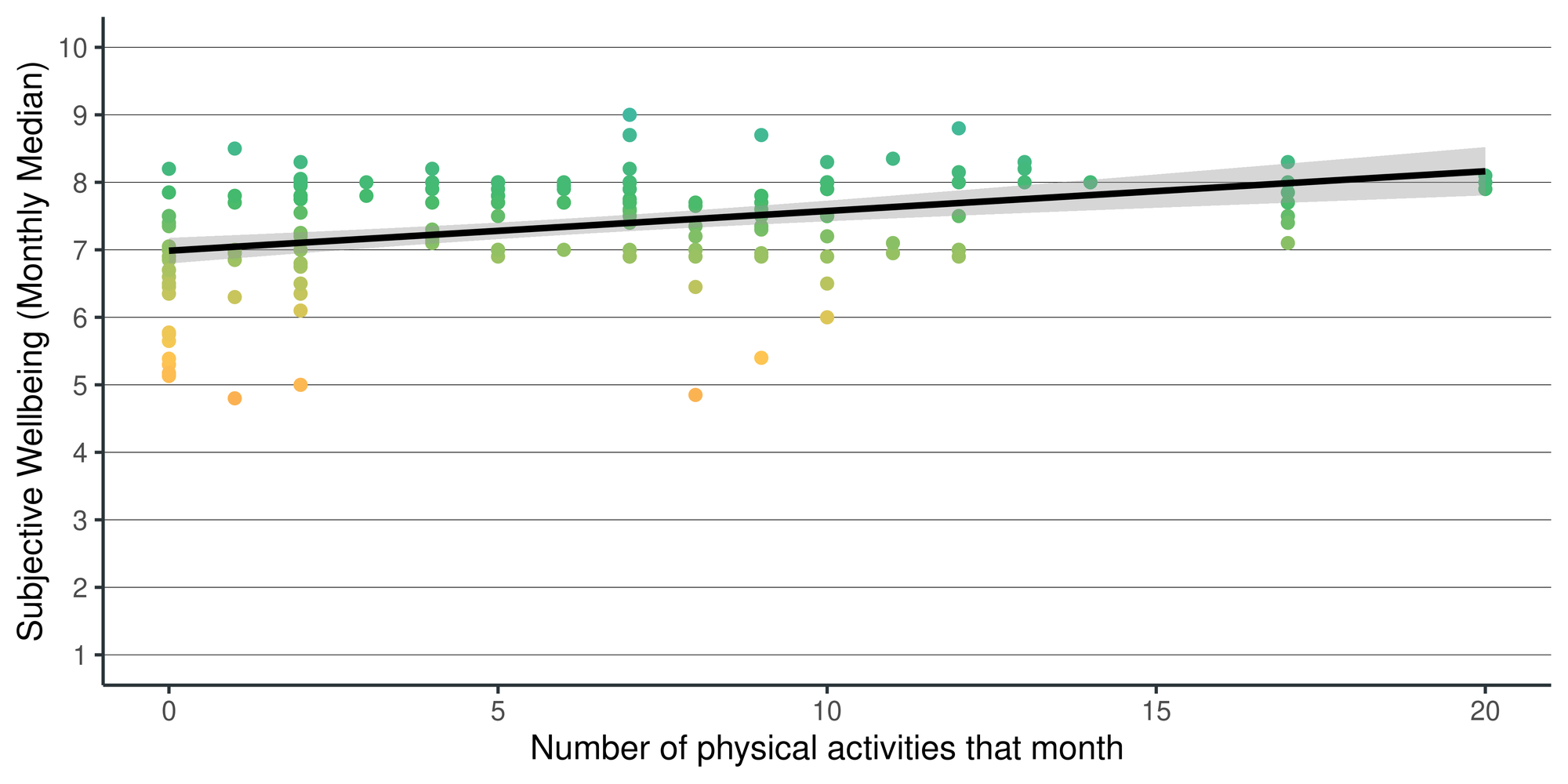

- Exercising often. Regular exercise one week meant regular happiness the next week. Irregular exercise was not super effective. It had to be regular. Keep at it until you feel you're making progress. Whether it was running, climbing or weightlifting, simply doing it regularly made me feel happier.

Did these things actually cause me to feel happier?

These are merely correlations. They don't show causation. It's possible that becoming happier gave me the motivation to overcome mental illness, to exercise and to spend time with friends.

But I think the opposite is true. Friends and exercise caused me to feel happier because I felt happiest after I saw them, not before. I felt accomplished at the end of a run, not the start. I felt great for having lifted weights, not that I was going to be lifting weights. It's likely that these behaviours became self-reinforcing over time. But at least initially, they caused me to become happier, not vice verse.

What didn't make me happier or unhappier?

- Moving countries. I moved to New Zealand in February 2020 and then to Singapore in March 2021. Neither effected my happiness per se. But it did take me away from friends, which made me unhappy. The moves also disrupted my gym routine, which reduced my wellbeing. So to the extent that moving countries had ferried me further from fitness and friends, it made me feel flat.

- Covid lock-downs. The Wellington lock-downs didn't effect my mental health. I was able to run, I was Zooming friends in Australia and we felt like we were in this together. However, Singapore’s heightened restrictions reduced my happiness about ten percent. I was not happy at not leaving the home, not learning French, not going to the gym and not meeting new people. It was a time of languishing.

- Holidays. I was no happier when I travelled alone. If anything I was more miserable. On holiday I was waking up at odd hours, dealing with cancelled buses and pointing ineffectively at the banh mi I wanted to chow down. However, when I travelled with friends it was some of the best days in my journal. Seeing friends and travelling together is wonderful, everyone should do it.

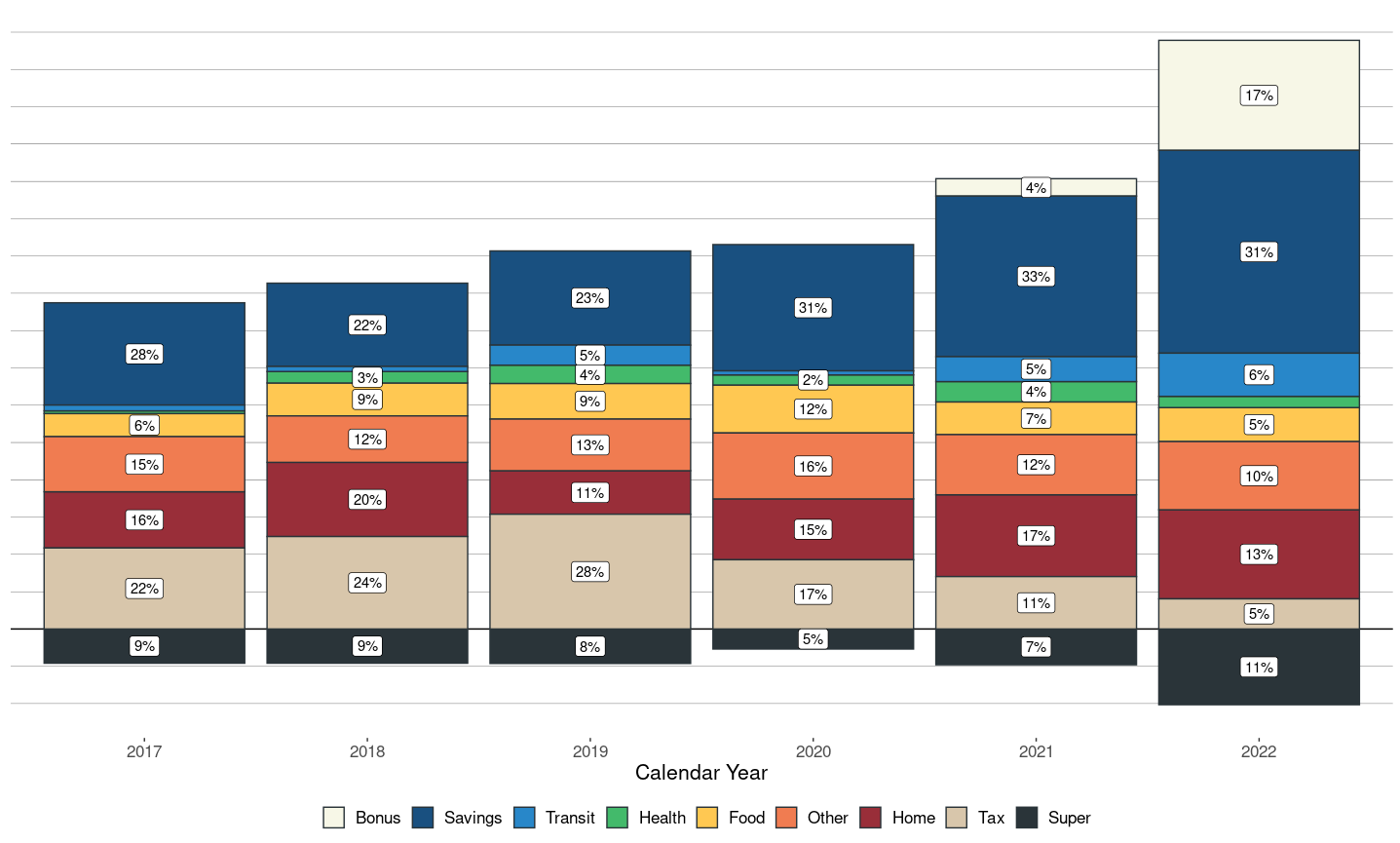

- Money. In and of itself, money didn’t make me happier. I did feel happier when I earned enough money to not stress about my finances. And I enjoyed the travel, language classes and consumer goods that money bought. But the money itself made me no happier.

If you have a mental illness, address it ASAP

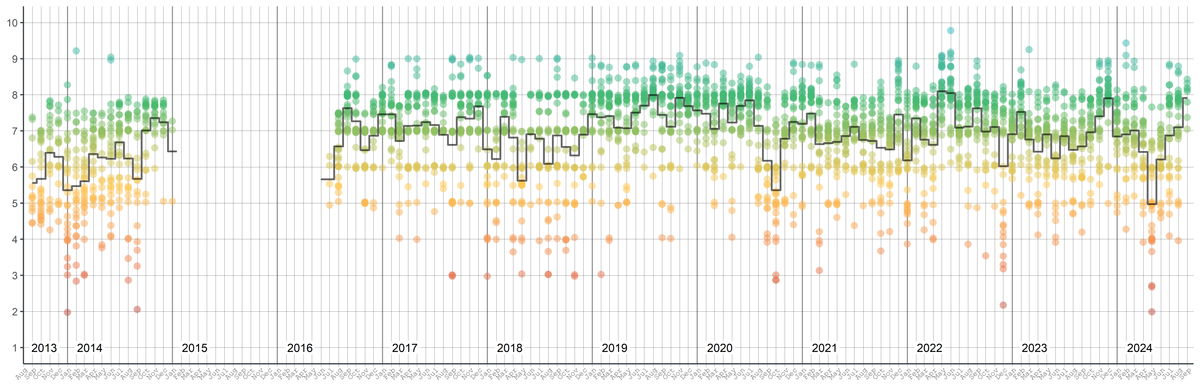

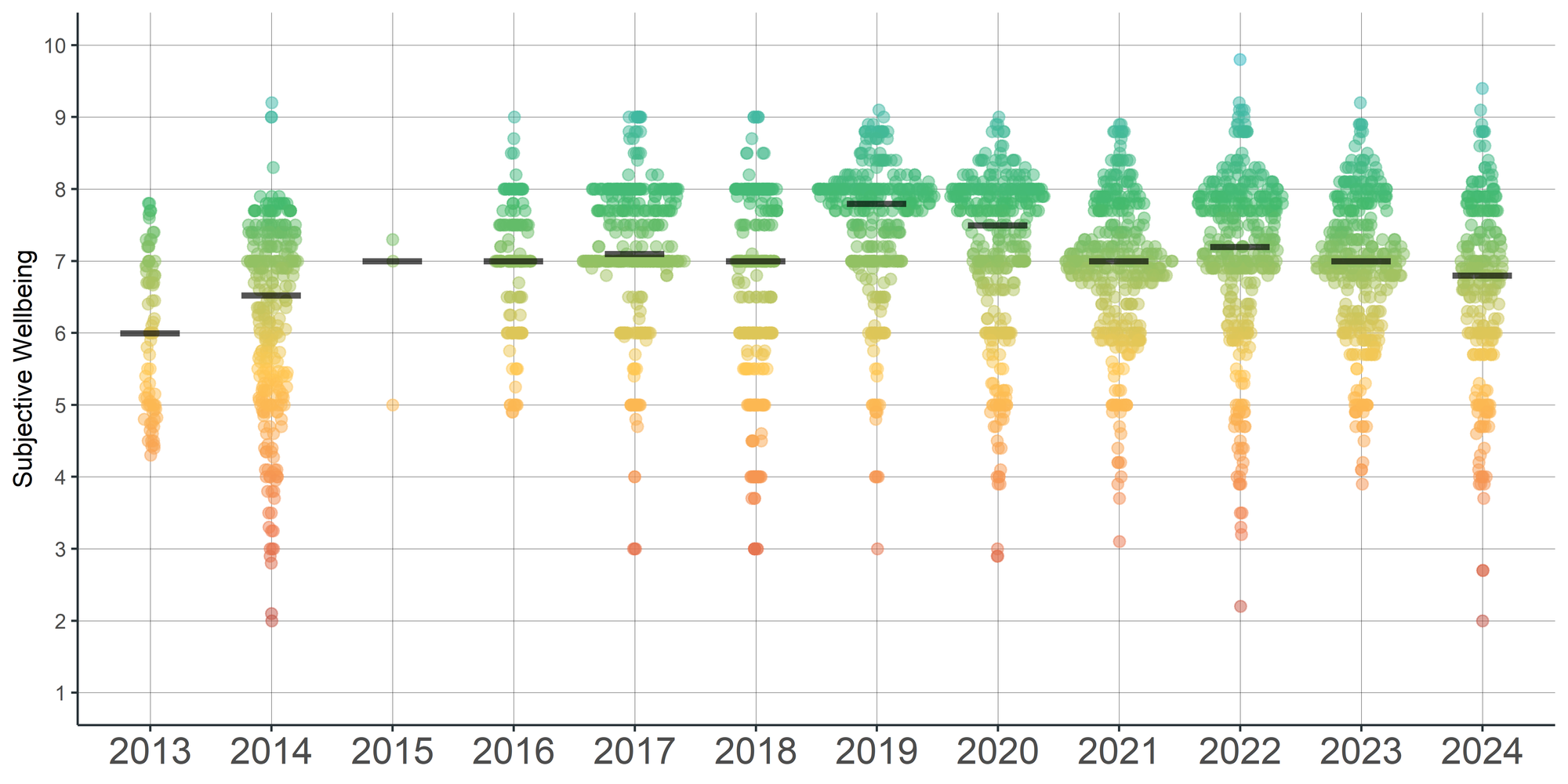

I started recording my wellbeing in 2013 because I experienced depression and anxiety. In early 2015 I started to feel better, my mood was stable and my work was manageable, so I stopped journaling.

In 2016 I had to start again. That year I had a rocky transition to a new house. I started a new job. I thought I was regressing back into mental illness. So I dusted off my empirically unsound rating scale, resumed journaling and haven't stopped since.

I had difficult months. Even when I had good mental health it was neither rare nor unhealthy to feel down in response to difficult circumstances. Some months at work were especially busy. Sometimes I caught a stubborn cold. And in May 2018 my father was diagnosed with terminal cancer. That was a tough month. It was normal to feel sad. I was adjusting to the fact that in the future I envisaged for myself, my father would no longer be part of it. But it was manageable. It didn't impact my functioning because I continued to exercise regularly, study French, and see friends often. Despite these challenges, by 2019 I'd lifted my wellbeing to an eight on average.

In February 2020 I moved from Melbourne to Wellington. This could have been a rocky transition, but I landed on my feet. I joined a new gym immediately so I didn’t lose motivation to exercise. I had a handful of friends already in New Zealand - I invested in our friendships and it paid off. I learnt to Scuba dive, which introduced me to even more great friends. Lock-downs were brief. Excepting a difficult time at work around October, my mood in New Zealand remained around an eight.

In 2021 I moved from to Singapore just before it entered heightened restrictions to fight Covid-19. These were as bad as their Circuit Breaker in 2020, but social activities were limited. It was hard to meet new people and gyms were closed. My wellbeing dropped down to just below seven. Like many of us during the pandemic, I was languishing. Only when I holidayed in France with old friends did my mood briefly climb just shy of an eight.

Things have gotten better in 2022, but I'm still not back to the halcyon days of 2019. And to be fair, aren't we all, to some degree, not yet back to out 2019 selves? These days I'm exercising more and learning French again. I'm taking regular holidays, but mostly alone. I simply don't have that many friends in Singapore. I've tried to fill the void by developing my data skills - the results of which you can see in these very graphs, dear reader. However, 2022 has underscored that there's no substitute for spending time with many good friends.

Spend lots of time with friends

My journal tracks my wellbeing very closely, but everything else it records is quite perfunctory. I'd be lucky to write two words about what I did, what I thought or where I went. For example, from March 10 to March 16 in 2014 I wrote nothing in my journal except my wellbeing scores. Then on the 17th I added the note "Went rock climbing", followed the day by the highly evocative "Started French class". I'm not going to lie, transferring my journal from page to spreadsheet takes time, and I try to minimise that time.

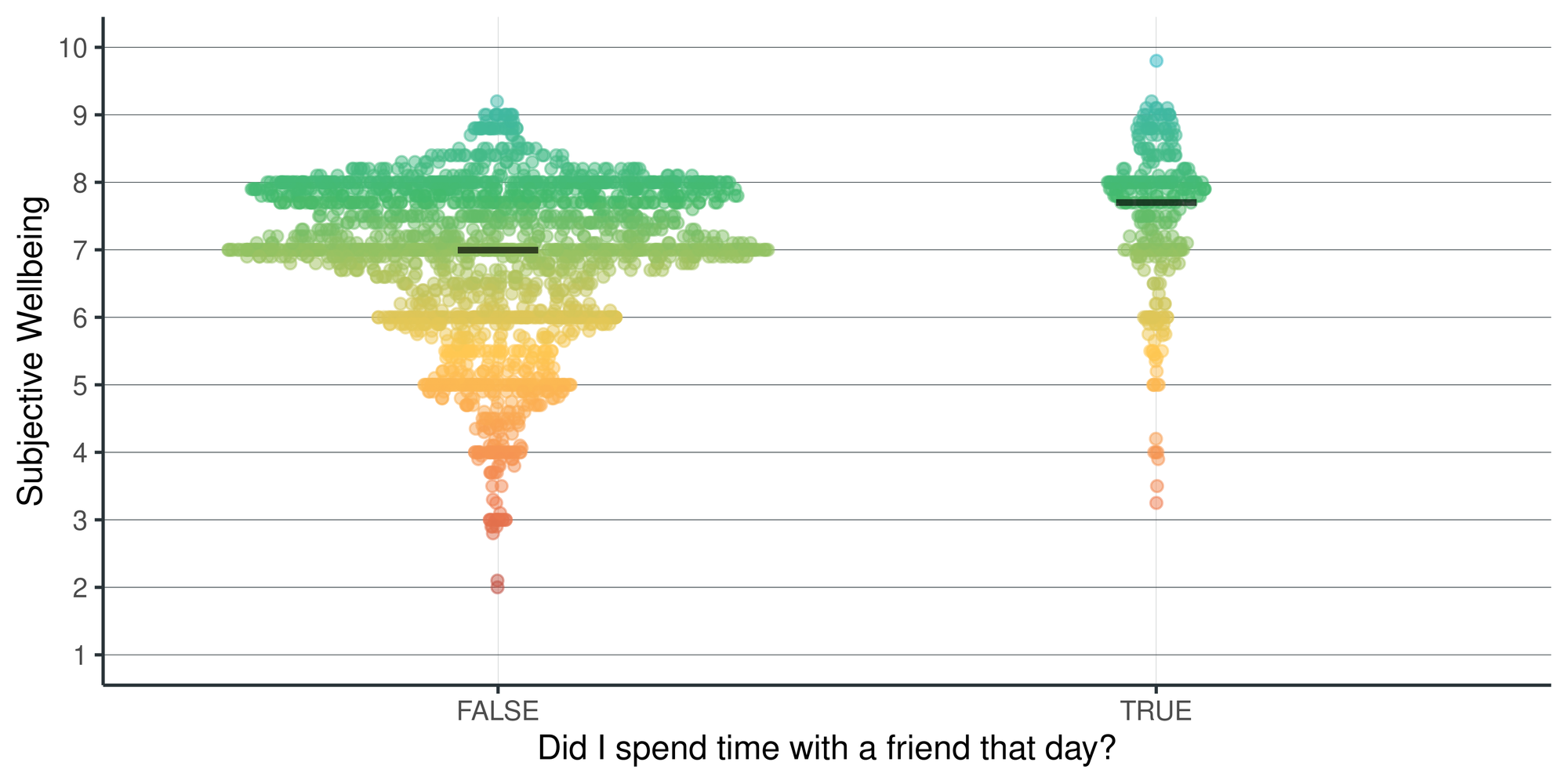

One thing I did journal regularly was seeing friends. Usually this was a short note that I "saw Jules" or "caught up with Jim". This is an undercount of my social interaction, because I saw my housemates every day, and my family often, but it's not recorded. After work drinks were written down infrequently at best. However, where I did note that I saw someone, it was usually because we planned to catch-up, and these were times I made the effort to be social.

The results are pretty clear. Days that I went out of my way to see a friend, or attend a social activity, were on average better days than when I did not. There's a lot of variation within these days. But the trend suggests that more social interaction was associated with more happiness.

Exercise regularly

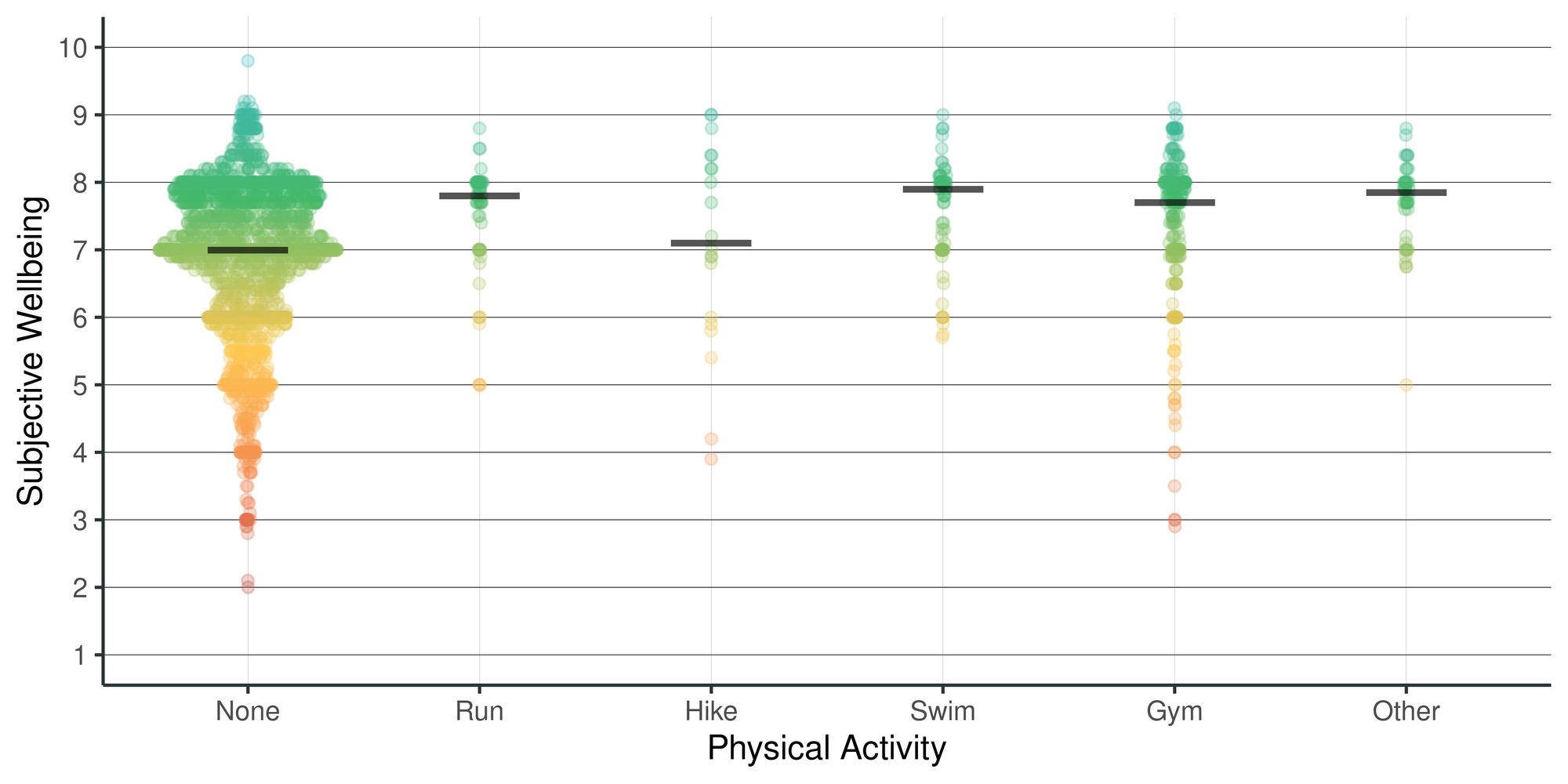

Regular exercise improved my mood considerably. Whether it was running, swimming or weight lifting didn’t really matter. What mattered was regular activity at least 3 times per week. Aiming for 4-5 physical activities per week was essential to hit at least 3 in practice because something always comes up to scupper your plans.

Hiking didn’t do much for my mood, mainly because every hike I did I was knackered. If I’d hiked more regularly, put in more cardio and never skipped leg day, then I might have felt happier after a long trek.

The first few weeks of a new exercise regime did little for my mood. But later on when I could measure my progress, I started to feel real good about it. Data points are few, but it seems like regular exercise put a safety net under my feelings. There were rarely long spells of depression while I was a gym shark (see above on causation). Day to day things could be tough but, when I exercised often, things snapped back sooner to a higher baseline.

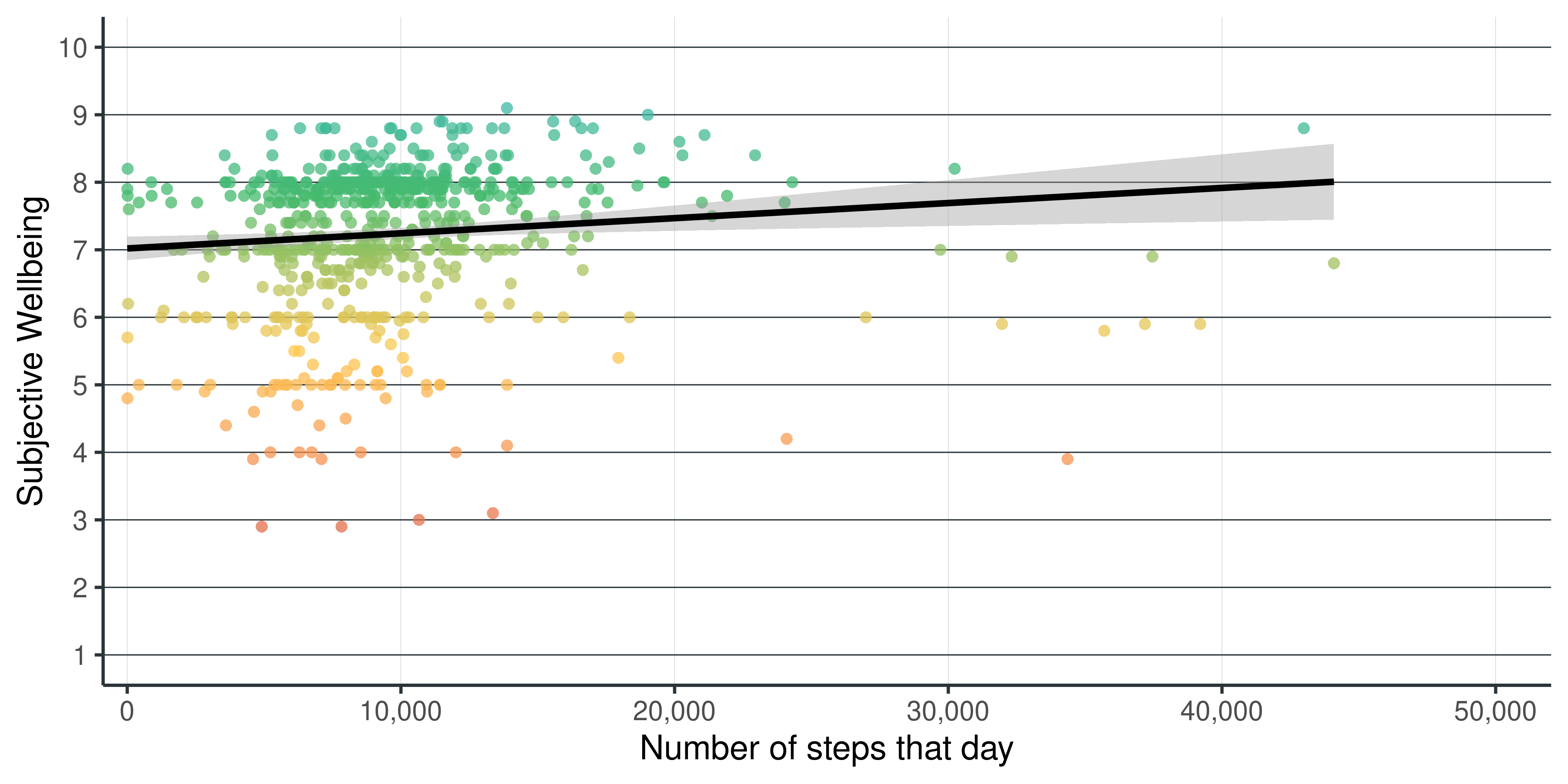

I also wear a fitness tracker. The tracker counts my daily steps. This allows me to match the number of steps I took that day with how I felt. What we see is that movement in general is only faintly associated with better wellbeing. On days when I walked more, my mood may have been slightly higher. While the correlation is positive, it seems to be driven by outliers, so I wouldn't read too much into this.

Exercise would not have improved my mood if I’d had depression. I would not have stuck to the routine so I wouldn’t have had any progress to feel good about.

You should monitor your mental health

I've found this exercise incredibly helpful for improving my mental wellbeing. I've developed a better sense of what helps me flourish and what I should prioritise in life. Tracking my wellbeing has not been hard. Taking 10 seconds every night to record your wellbeing is a great habit. If you're not checking in on your mental health regularly, you should start doing so. It makes a difference.